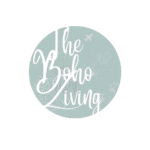

A slow-paced, mostly unplanned journey to a land that blends the culture, chaotic charm, and the untainted beauty of the mountains, Central Asia and Europe, that was my 3-country Caucasus (Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia) trip. I spent 21 incredible days exploring these neighbouring gems from India — wandering old towns, sipping wine with locals, taking many a Marshrutka across scenic mountain passes, and losing track of time in flea markets and fortress towns.

Even though Georgia and Armenia were part of my 3-Country Caucasus (Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia) trip, this travelogue focusses only on the Georgia part of it.

Georgia and Armenia are part of the Caucacus region of Central Asia, countries bordered by Russia, Azerbaijan and Turkey, making them a perfect amalgam of Europe and Asia, a combination I’d first experienced on my Turkey trip a couple of years earlier. However unlike Turkey and Azerbaijan, both Georgia and Armenia are Christian-majority countries and their culture is a departure from the middle eastern flavour of the former.

Here’s my 10-Day Itinerary for Georgia and Armenia

Day 1– Crossing from Azerbaijan into Georgia through a hairy immigration

After a 2.5 hour scenic drive from Sheki in Azerbaijan with the people I’d met in the hostel, we arrived at scenic Georgian border. Even though I had a multiple-entry Georgian visa and other required documents prearranged, the immigration personnel ran through my passport a little too throughly and ran me up and down rather too intensely for comfort. (I’d heard enough stories of Desis having been deported from Georgia for no reason at all to be scared for a minute!) But all worked out and through I was to the other side, after walking through what seemed to be the longest open air tunnel. That was the overland border between Azerbaijan and Georgia, two countries, similar and yet different, sharing a soviet history, the Silk Route, and the Caucasus mountains and friendly neighbours for the most part. (With Armenia, it’s a different story.)

On the other side was Lagodekhi, a nondescript Georgian town best known for being the first port of entry for travelers that enter Georgia by land from Azerbaijan. Our remaining Mannat and dollars traded for Georgian Laris (or GELs), we hired a cab and made straight for Sighnaghi, a quaint town in the Kakheti region of Georgia, famous for its vineyards and wineries.

(If you enter Georgia by air through Tbilisi, you can still come to Sighnaghi as a standalone trip or as a part of a curated winery tour.) The two-hour drive to Sighnaghi was mainly through a thin, flat stretch of road in the plains, with the lush Caucasus mountains always in the background, however the number of roadkill dogs splayed all over wasn’t the most welcome sight.

Wining and whining in Sighnaghi

Sighnaghi is a charming hilltop town in eastern Georgia’s Kakheti region, distinct with its cobblestone streets, pastel houses with wooden balconies, and sweeping views of the Alazani Valley and Caucasus Mountains, and better known for being a hub for Georgian wine culture, offering easy access to family-run wineries and traditional wine tastings. I was putting up at a homestay with a family of wine growers that consisted of two college-going girls, their parents and a lovely granny who welcomed me with a homely lunch of boiled corn, cooked kidney beans and the famous Georgian wine, available by jugs! While I savoured the hospitality, a rare thing on my trips abroad, the girls, gorgeous and spunky, who studied in a university in Tbilisi, chitchatted. They held forth (in perfect English) about the state of Georgia, the country’s bleak employment situation, their own ambitions to be able to travel abroad someday- which isn’t usual for Georgians, and their society in general, and I realized how similar it was to the one in India. For one, we discovered that both the Georgian and Indian societies — one mostly Hindu, and the other mostly Christian — are essentially conservative and look down upon skimpy clothing, love to gossip about whose son is seeing whose daughter, and that Georgians watch Indian soap operas with great relish! After a heartening chat with the girls and feeling stoked about being in Georgia already, I headed out to make the most of the remaining sunlight in the day – maybe a little too much sunlight for comfort. At around 38c and a blazing direct sun wasn’t exactly the retreat from the Rajasthan summer I was hoping for, but in Georgia, a granny selling freshly squeezed pomegranate juice was always around a street corner to ease things up.

As I usually do on most of my trips, I headed out for some supermarket browsing and spotted a SPAR — a comfortingly familiar sign in a foreign country. The AC inside was really helping as were the prices! I ended up buying an enameled dog bowl (with a motif of dog that looked just like Peanut) and some spoons – you know as travelers do. But the real deal was right by the counter — dozens of wine bottles lined up at as low as $2 each! Even to my Indian price sensibilities, these were a steal. It’s a pity that I am hardly a drinker and wasn’t carrying checkin luggage so I couldn’t port all this delicious and cheap wine for back home, but at another artisanal boutique, i did buy a bottle of Kindzmarauli wine painted with a beautiful sculpture of Niko Pirosmani, which as I learnt were one of Georgia’s most prominent wines and celebrated artists, respectively.

I continued to navigate through the charming old town done dirty by the current weather, ending up at a Great Wall of China-like fortress that was full of…Chinese tourists. The fortress was punctuated with stone watchtowers the likes of which I’d see in Svaneti later. I climbed a couple to sweeping views of the barren valley in the front, and then retracing my steps back, stopped by a cafe to sample the famous “Kachapuri”, an egg-and-dough based delicacy synonymous with Georgian cuisine, but skipping it as it didn’t have a vegan or even a vegetarian/egg-free version. Ah well, the supermarket dinner of noodles and fruits to the rescue again. As the sun was setting, the fairytale town was coming into its own, the patina-ed spire of church glowing against red-roofed houses, streets grown quiet, except for the odd off-season tourists like me, and a street dog who wouldn’t leave me alone, forcing me to part with some of my Indian snacks! Ah well, guess I was the designated stray dog feeder across borders!

The Georgian delicacy I did feast on though was a glass of wine at a charming wine house perched on the edge of a street. It was just me, the wine, and the beautiful setting sun against the valley in front of me, and it finally felt like the slow trip that had probably evaded me so far. It was also a good breather before the hectic day of wine tour ahead.

Day 2 – Of Vineyards, Qvevreris, wine cellars and wine companies in Georgia

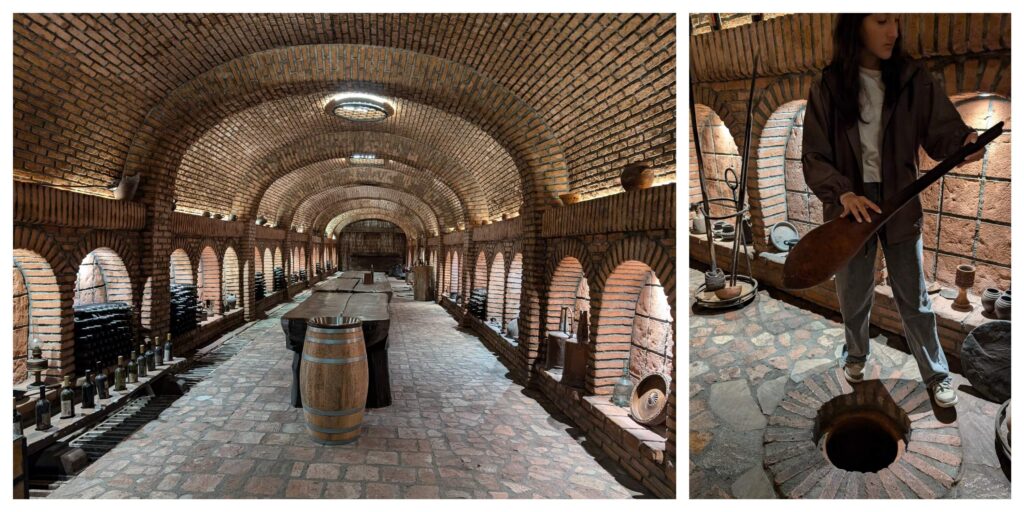

Even though one usually associates wine with France and Portugal– in fact myself having been on a vineyard tour in the French Bordeaux region on a previous Europe trip exactly a decade earlier and a Porto wine tour on my Portugal trip, just a couple of years earlier, Georgian wine is one that leans on an age old tradition — making wine using clay pots called Qvevris that are buried underground for fermenting.

I signed up for a full day guided wine-tour with the homestay patriarch himself as the guide/driver with three others from the homestay, and made to our first stop. A wine factory’s rather fancy visitor centre that had a simulated version of a traditional Qvevri with a less-than-enthusiastic guide hurriedly walking us through the history of Georgian wine making and jumbling most of it up. (WHAT is it with disgruntled Georgians everywhere?) I had to rely on the internet for a better explanation.

As per Georgia’s traditional winemaking, after harvesting, grapes (including skins, stems, and seeds) are crushed and placed in the qvevri to ferment naturally. For white wines, extended skin contact creates amber-colored wines with rich tannins. The wine is aged in the qvevri for several months before being decanted and bottled. This ancient method, dating back over 8,000 years, produces bold, earthy wines and remains central to Georgian culture, especially in regions like Kakheti. While modern techniques exist, the qvevri method continues to define Georgia’s unique and historic wine identity.

Having found the experience a bit contrived, we left for the next stop on our way through the idyllic but crazy Georgian roads to another big wine hub. The epicentre of all commercial Georgian wine — the Kindzmarauli wine factory.

It started with a 30-minute wine tasting session in which we were served 4 samples of wine — and Georgia produces over 300! including the famous Saparevi and Rkatsiteli varieties. Putting on my faux wine connoisseur best and swirling and swishing my glass around, I concluded that Georgian wine, especially the amber Saparevi was delicious, and left me feeling a bit buzzed for a few minutes later. These heady minutes were spent touring the sprawling quarters of the factory including watching giant 1 million litre steel containers filled with wine, who along with the Qvevris, were quietly doing their own thing. And then in a version of “exiting through the gift shop”, we came out through to the in-house store with choicest wine ranging from $1 to $1000 a bottle depending on origin of the grapes, duration of ageing, and your knowledge of wine.

The wine run was only momentarily broken by a quick detour to the 9th century Bodbe monastery –located on the steps of wooden hill – a significant monument for religious Georgians and renovated since Georgia’s independence from the USSR in 1991. In one of the rooms of the church, what do I see? A hall full of what was once a functional Qvevri! Alcohol was made in a Church! Not blasphemous at all in Georgia! (or anywhere?)

Ending the tour with another quick visit to a vintage wine museum/wine cellar, and a quick sprint across an open vineyard to come back right to the source, I was all wined-out.

The guide dropped me at a bus point on the highway from where I’d take my first Marshrutka in Georgia. (By now I was quite familiar with these soviet-relics ‘Marshrutkas’ which were basically reasonably priced private-public vans (or tempo travelers of India) to travel across cities or within the city and my saviours during my Caucasus trip.)

I hopped on one to Tbilisi, the Georgian capital city after almost two days in the Khaketi region.

The drive was smooth, passing more vineyards and wine cellars on the way, loading and unloading locals, all curious to see a foreigner girl sprawled a little too comfortably in their local commute! But could I blame them? I was probably the only solo Indian traveler in Georgia I’d seen so far, leave alone in a Marshrutka full of people who barely spoke any English or had barely heard of my country!

Arriving in the crazy, chaotic but charming Tbilisi

After being dropped in the middle of a busy and chaotic metropolis, I took my first metro of the trip and discovered that the escalators in the region ran up to 100-150 feet deep as they doubled up as bunkers during the WW1 and 2! Shortly after navigating the metro, petting a few stray dogs and politely warding off a hobo, I arrived in Rustaveli, a bustling, if a little run down metro station buzzing with buskers, street hawkers, artists, and young and trendy Georgians returning home from work. I just about caught a setting sun and headed to my digs for the next 4 days in Tbilisi.

My hostel was a seedy lil dwelling in a backstreet, but its location made it logistically perfect. Sitting at one of the balcony-propped tray tables in the hostel’s cafe, I calmed my travel-weary bones and wine-addled mind with a cup of premix chai from India, cup noodles from Spar and a chocolate croissant from the supermarket next door! Kinda an anticlimactic dinner on a day that revolved around fine wines just a few hours earlier! Adding to the strange vision was me, a bespectacled solo Indian girl, surrounded by Russian, Ukrainian and Central Asian men, some of whom definitely looked like they were on the run from something back home!

Day 4 – Being my own guide in ‘Warm Place’ Tbilisi

Unlike my other trips, I was in no hurry and there were no specific sights to tick off my checklist on this Georgia and Armenia trip. So I decided to wake up whenever my body decided to, treat myself to a slow breakfast of muesli, fruit and croissant, and headed out only about 2pm. The sun was at its hardest and suddenly being out and about didn’t feel like the best decision, but still I was traveling abroad and staying indoors would be a waste of my hard-earned foreign exchange and visas! So invoking my Rajasthani roots, I braved the heat, learning soon after that ‘Tbilisi’ literally means ‘Warm Place’! (How about boiling?) After acquiring a SIM card and some more food, I headed straight for the busy Liberty Square area, the beating heart of Tbilisi where most of the cafes, bars and historic sights, if any are located. Even though I’d seen it in parts in the commutes so far, Tbilisi was finally sinking in.

Similar to Baku in Azerbaijan, where I was just a few days earlier, Tbilisi too seemed like a place in transition between its storied if dark past and a new beginning. It was all modern skyscrapers, wide avenues, and yet crumbling but beautiful old buildings, Renaissance relics, and soviet Bloc architecture forming a unique entity. But unlike Baku, which felt somewhat contrived and even artificial and disingenuous to its middle-eastern and central Asian roots in its scramble to be a lovechild between Dubai and Paris, Tbilisi seemed more ‘real’ with a lot of character. There was a quintessential bohemian vibe to the place and I loved it for it. Tbilisi was still very European, with beautiful ornate buildings that had seen better days, tree-lined wide streets, but full of street dogs, poverty, cheap prices, and somehow very similar to a metro city in India. Perhaps also adding to the familiarity was the curly-lettered Georgian script which looked exactly like a South Indian language like Tamil or Kannada, but sounded nothing like either!

Following an itinerary I borrowed from a city tour website because I couldn’t be arsed joining a walking tour this time, I continued navigating Google maps through to the downtown area, located one of the few sightseeing tropes – A kitschy Clock Tower with a bunch of lopsided and mosaiced patterns, clicked a couple of token photos and walking past the rows of open-air, hipster cafes in the Erekle street, ambled into a cast iron statue of “Tomada”, a toastmaster who raises a toast and signals the start of a drinking party – a Georgian ambassador of sorts. Later on, I was scheduled to meet Steve, an American solo traveler I hung out with in Baku a few days earlier who was also on a Central Asian/Caucasus trip. We climbed up the imposing 20-meter high steel Mother Of Georgia statue and then took the cable car above the river divided by the very modern, glass “Bridge of Love” straddling an ancient city on one side with its antiquity, fortress walls, and many patina-domed monasteries and a buzzing modern district with funky skyscrapers and even an EY building on the other — quite the perfect symbol of Tbilisi itself.

Post some walking past the old quarters, Steve got us to a quaint wine house with a view, where I had some Georgian salad with walnut dressing – a Georgian delicacy – downed by of course a glass of wine which I now knew to be the inimitable Saperavi. Then as we were parting, Steve — nearly twice my age — invited me to his place to ‘spend the night.’ I’d sensed this in Baku too when post a walking tour, I was invited to his Airbnb “because he had AC” (which is admittedly plenty of motivation in 40 degrees!) But this time, it was clear that Steve thought that I was available and DTF a man my father’s age! Ah well, I guess that’s what we solo female travelers can come across as when just being friendly and open to hanging. I’d had a similar experience in Baku with an Azerbaijani local, much younger however, just three days earlier which I’d also narrated to Steve. Part amused, part cringing, I walked the 3kms back to my hostel, stopping every now and then to watch a street performance, stumble into a souvenir or art store or pack whatever vegetarian snacks I could spot. After doing a lot of back-of-the-envelop calculations, I decided to head to Mestia the same night and got on an overnight bus to Zugdidi, the last major town before the start of the mountains. For a change, this wasn’t on a Marshrutka, but a fancy Volvo bus but having had to scrunch up on a seat for 7 hours in the frigid bus made me miss the sleeper buses in India – look, India may not have the best infrastructure for the most part, but when it comes to buses, it doesn’t get better than our AC-cabin-with-a-TV-wide-berth-sleeper buses of India. That’s a hill I’d die on.

Day 6- Zugdidi, Onwards and upwards to the mountains of the Svaneti region

The bus pulled into Zugdidi at 5am, a time rather inconvenient as the first public Marshrutka to Mestia would depart only by 8. But deciding to try my luck anyway, I started to walk in the general direction of the railway station. It’s at this moment that any other normal person would’ve, excuse my French, s**t their pants! Not only was I walking alone on an isolated street in a foreign country in a small town, but dozens of feral dogs barked around me. Knowing better, I continued to tread ahead, petting or making “pch pch” sounds at the furry beings, now circled around me by the dozen, calming them instantly! Even the locals who spotted me do that were probably surprised that I wasn’t running away or freaking out at the “attack” but handling it rather well. And this is where I drop a bit of street dog wisdom.

Street dogs are mostly harmless, even if they look or sound otherwise. They have a right to bark at strangers, but all you have to do is assure them you’re harmless, do your own thing and they go right back to their own business, or better ask you for nothing but pets and some food. I’ve never had a dog bark at me for longer than a few seconds because they just know I’m their friend, even if from another country.

Passing through a local produce market that was just about coming up, I saw no signs pointing to Mestia, but following a random travel blog, I navigated to the railway station anyway. There, a group of rowdy young Russian guys were hanging out, just screeching and playing around, and asking them about the whereabouts of a transport to Mestia yielded no results due a language barrier. I was once again left to my own devices — 6 in the morning, hungry, sleep-deprived, tired from the awful bus ride, and a bit angry with myself. Should I have just stayed back in Tbilisi instead of going through this tedious and rather expensive detour for barely two days? So many decisions and what ifs were to become the order of the day on this trip.

I continued to walk in the general direction of Mestia as I battled with these intrusive thoughts, and just then a private car stopped by me and in part sign and part English asked me where I was looking to go. Bingo! He was also headed to Mestia and could drop me. But could I trust a rural Georgian man in a hatchback – seemingly the Georgian equivalent of a Maruti 800 — who spoke no English to take me on a 5-hour trip through presumably treacherous mountain roads all alone? And just then another local girl got into the car and signalled me to join away. I hope I wasn’t going to land in some sort of scam. Well, fuck it, i’ve done more adventurous/risky things, I didn’t have that many options and leaving now would be optimal to make it to Ushguli by noon. So I hopped into the car, cold as it was, and prayed that there were no ugly surprises ahead.

There weren’t except that the driver demanded more money than the decided fare. Even though I was bummed, i couldn’t really be that mad. This was mostly a semi-private chauffeur driven ride through some hairy mountain roads and I was just glad to have made it.

Arriving in Mestia at around 11am, I started to look for ways to get to Ushguli. Now most travelers do a scenic trek from Mestia to Ushguli or even beyond, a route that could take anywhere between 3 to 5 days depending on one’s speed and style, but since I neither had the time nor the company to foot it, the easier option was to take a 2-hour cab or bus to the place. Hoping to find a cheaper deal than having to shell out nearly $50 for myself, I waited hours but nothing materialized and eventually I shared a $100 cab with two Chinese girls, cursing myself for not having done this sooner and have a longer day in Ushguli.

A day and night in the bizarre but beautiful Ushguli

We arrived in Ushguli at 2pm, giving a solo Spanish trekker a lift halfway on the way to Ushguli with whom I ended up sharing the room that night.

Ushguli is a remote mountain village in the Svaneti region of Georgia, nestled at the foot of Mount Shkhara, the country’s highest peak. One of the highest continuously inhabited settlements in Europe and now a UNESCO world heritage site, Ushguli is renowned for its dramatic landscapes and medieval stone towers, known as Svan towers built between the 9th and 12th centuries, used to protect families from invaders and avalanches. Arriving there at two pm didn’t leave much of the day to explore, so the trekker and I scrambled for a room. Accommodation in Ushguli is sparse and mostly consists of family-run homestays, but that’s soon changing as signs of construction were all around us. Perhaps the place would look nothing like this a year later, so we were just glad we were the last batch as it were to catch Ushguli in some of its remote and rustic essence. We got a basic room with a Svan family that looked like they’d never stepped out of their house, leave alone that village. Understandably, they spoke no English, looked like they belonged to another era, as did their house with a slew of animal heads and hides displayed on the walls like trophies. My vegan sensibilities aside, hunting isn’t a transgression, but a way of life for the Svans, as it is for remote communities around the world. It was also perhaps the only form of entertainment before internet arrived.

I walked around, in no particular destination, until I reached a ridge with a view of snow-capped Shkhara mountains and rolling green valleys in the front and wild dogs and out-of-work mules frolicking about. Beautiful as it was, I wasn’t particularly impressed with the scenery or the vibe (Having spent over a month in India’s 2500-meter high Himalyan town Dharamkot just a month before my Georgia trip didn’t help), so almost disinterestedly, I sat myself at a vantage point from where I could see the Svan Towers, the one unique thing about this region, and later chatted up a French family of four who’d been traversing the Caucasus in their RV.

And just then, a streak of reflection and maybe a tinge of sadness came over me. Was solo traveling beginning to finally lose its sheen for me and maybe had me pining for traveling with my partner, or a future family? What was even the point of seeing all these pretty sights, experiencing these moments, but not having anyone to share them with? Or worse, maybe travel was beginning to feel like just a different kind of struggle, rather than an escape from it?

Clearly mentally I wasn’t too into the moment, there wasn’t much else to do, it was getting cold and me old, so I trudged back to the homestay and tried to have a conversation with the homestay matriarch. I happened to open the commercial-sized fridge in her kitchen and lo! What do i see there? A whole-ass COW – frozen! When I was done recovering from the discomfort and shock of it all, I learnt that the local Ushguli families — dairy dominant as they are – eventually slaughter their own cattle and preserve their meat for all of winter when the roads to Ushguli get snowed under and barely any vegetation grows in the region.

As though all the animal-skin covered walls weren’t enough, this sight made me lowkey upset, but I couldn’t really resent them. After all, Indian dairy families do the same, if not directly. After the cows are done milking, they’re eventually let off on the roads, or worse sold to butchers to eventually turn into beef and leather. (Sorry about the segue into “why veganism is the right thing” you didn’t ask for.)

Next morning, from my room’s window, I had one last look at the picture perfect view of the thin and clear stream against the row of 8-10 Svan towers and the Svaneti mountains in the background, admiring the raw beauty, with imminent signs of change upon the region. The brief moment of calm was amputated by a mad scramble for someone, anyone, to get us back to Mestia without asking for a kidney. We settled for $50. In Mestia, a rare bit of luck struck and I found a guy heading towards Zugdidi who offered a drop for a steal, again getting my cynical self all charged up. The guy was smoking hash while driving in the mountains only phased me ever so slightly. But oh well, this trip had been adventurous and yet safe this far. I had to keep the faith in the fair gods of travel.

A shopping rampage in a Chinese market in a Georgian tier-3 town

By late noon, after a quiet uneventful ride listening to mostly Greek beach music in the car and small chitchat with the driver who’d apparently come to drop a rich Polish family to the mountains, I was back in Zugdidi, the sun hitting harder than ever, and the flea market that I’d passed the day before, laid out in full glory. The backpacker in me took a backseat and the shopoholic took over and I went on a rampage. The Zugdidi local market was full of unassuming shops hawking household knick-knacks, western clothes, trinkets and household utilities — mostly Chinese dumps –cheap fancy baubles that I couldn’t get back home ever since we cracked down on Chinese imports. So I shopped for Made-in-China Turkish tea kettles, Balinese cutlery and heck even some unnamed whatsitsname — as much as my Georgian laris would allow.

Sunburnt, on an empty tummy and an overloaded bag full of junk, but happy because of the shopping ‘finds’, I boarded the train back to Tbilisi – and my first on this trip so far. The streak of poor transport continued, and the 3-hour train ride took 6 hours, with no internet for the most part, no books, just a bunch of noisy kids and their irritated moms for entertainment for the trip. Not the best train ride of my life, but I was just glad to be heading back to Tbilisi and my hostel which by now had begun to feel comforting and familiar.

But rest wouldn’t come easy on the remainder of this trip. Next morning, I had to leave for the Armenia leg of the trip to leave a couple of days for Tbilisi in the end before my flight back home.

So at 7, I headed out of the still sleeping hostel with a day pack, and took a metro to the station from where i’d find a Marshrutka to go to Yerevan. By now, I was a bit of a Marshrutka expert and found just the right one without much hassle and even managed to communicate enough to the driver to let me stop by and pack some snacks for the ride!

In the interest of brevity, head over to my blogpost on Armenia, as short as that leg was, as I continue about Georgia on this one.

Day 10- Back to Tbilisi and discovering treasures

Having arrived back in Tbilisi, after a lil detour to Armenia, late at night, there wasn’t much I’d managed to do except for a stroll near the hostel, picking up some souvenirs and chit chatting with my hostel mates. But today was my final day in Tbilisi and of this trip. The August heat wasn’t relenting but I was on a mission. I put on the lightest white cotton dress I had, perhaps one meant for a day like this, and walked on the now familiar streets to head to the Dry Bridge Market – a legendary soviet era flea market that still thrived and went on everyday in the heart of Tbilisi.

I stopped by an artsy college district and a theatre with a statement staircase with the most beautiful, intricately painted terracotta-hued tiles. After doing a bit of self-portrait sesh (but mainly trying to avoid heading out into the sun), I walked to the Dry Bridge market. It was still being set up, but just as I’d read, it was a smorgasbord of curious curios! Cutlery that apparently belonged to Stalin? Check. Brass busts of Slavic women? Check. Random fittings and plumbing parts, check. Paintings by young artsy Georgians, you got it. I picked up an intricately painted ceramic wall plate — allegedly from the 50s — but quite a bargain for a 70 year-old antique at $10 that graces my home back in Bangalore now, and a pair of silver handmade earrings – ones I still wear often. I wanted more, but my one bag was already overloaded from the spoils of Zugdidi and Sighnaghi, and I still wanted to buy some paintings from an old woman at the metro station. So I extricated myself from the temptations of this treasure island and headed to what was one of the best finds in Tbilisi so far.

Pretending to a digital nomad at Fabrika

It’s hard to describe exactly what Fabrika was. A gigantic building which was a factory back in the soviet era converted into a hostel, a coworking space, cafe, a collection of vintage boutiques, and a hipster hang all rolled into one. With a huge stone sculpture plate and a million murals and graffiti on its facade, Fabrika was nothing like I’d seen before. I had to check it out on the inside. Pretending to enquire about the rooms, I walked around, soaking in its vast warehouse aesthetic, past the plush velvet chairs, bean bags, large monsteras, and all sorts of vintage/artsy furniture and into a red LED lit washroom! Scattered around me were bohemians, artists, hipsters, and of course the laptop and man-bun toting ‘digital nomads’ hunched over their Macs. Even though I didn’t have a job during this trip, I missed my own because sitting there without one or having any real networking needs made me feel like an impostor. Still, mustering all the faux confidence I could, I ordered myself their artisanal roasted coffee and a vegan sandwich from the bar-style inhouse cafe and sat myself at what seemed like a long, communal table. I struck a conversation with a young Turk, probably my first real interaction in this trip with a non-local, who was in Tbilisi on a ‘workation’ – apparently 90% of the people at Fabrika were. I wasn’t surprised as Georgia has been racking up a reputation as a digital nomad hub in the recent past. Its strategic location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia and clearly a culture that’s the same, relatively cheap prices and a 365-day visa (for non Indians of course) and plenty of cafes, does make for an attractive destination for remote workers. Spending sometime at Fabrika did make me consider coming back for a longer stay, a workation. But for now, I had to continue on my sightseeing and make it back to my hostel as I had a flight back early next morning.

Walking aimlessly, buying many an iced tea from the supermarkets to survive the sweltering heat, hopping on a couple of local buses, I hauled back to the Mtatsminda area and climbed up the Sameba or the Holy Trinity Cathedral, a magnificent if a relatively new (2004) building. Perched on a hill and over 300 feet high, the imposing church was a vision in beige under the bright sun, with its three A-shaped awnings (i’m sure there’s a better architectural term for what I’m trying to describe!) leading to the golden dome, visible from anywhere in the city. Inside, I was awestruck at the beautiful frescos, elaborate columns, and mesmerized by the harmonious and unique chanting I’d now noticed for the third time in Georgia. Hard to explain in words, but the singing follows a rhythmic pattern of chants, creating a surreal, almost dark atmosphere inside the Church, reminding me of the vedic-chanting back in the temples in India.

The sun was setting and as was my time in Georgia so I drank the views in (and my fast depleting water) a bit harder, brushed past the famous Sulphur Baths, wishing I’d spent the noon soaking in one of them instead of in my sweat. For the final time, I walked back to my hostel past the tree-lined Rustaveli avenue, taking one last look at all the beautiful, decaying buildings of Old Tbilisi as they faded behind me. Packing one last croissant and at long last, a mushroom Khinkali, I boarded the airport bus, just as a full moon appeared in the skies. I was leaving Georgia just when the place was beginning to feel familiar, and if I’m honest grow on me.

Well, there’s always the workation to come back for. At the airport, there were stray dogs inside, right under the seats in the waiting lounge. Not being shoved out, resented, but sleeping comfortably. I was sold. Georgia had its heart in the right place, and a lil bit of mine in it.

I said a mental “Madloba” and got on my 4-hour Indigo flight full of Indian students back to Delhi.

3 Comments

It was good content. It helped me a lot.

I was looking for tips and ways to plan a solo adventure in Georgia and Armenia, and I’m so glad I came across your blog with all these helpful details. Your photos are amazing

Thank you for detailed information. I am not going to Georgia because I want to club it with Armenia and lack of Europe visa is making things difficult.